What will happen to interest rates this year? We’ve developed a modified version of the Taylor Rule which might have the answers.

Monetary policy has a major influence on investment returns – whatever the asset class. Yet forecasting the path of official interest rates is far from straightforward. That’s particularly true now, given the debate over how fast and how far US and the euro zone should cut rates as inflation eases.

One useful tool for estimating the trajectory for interest rates is the Taylor Rule. It has been around for decades but is still one of the most useful models for guiding monetary policy when the credibility of the central bank is at stake. Its great strength is its simplicity. It states that nominal base rates should be close to the rate of nominal GDP growth plus or minus a coefficient that measures how far inflation is from the central bank’s target and how growth is faring relative to its long-term trend.

However, the rule’s simplicity comes with limitations. Not least because central banks consider many other factors besides growth and inflation. We have therefore devised our own modified version of the Taylor Rule, which we believe fits the reality better.

Our model suggests that rate cuts in the US and the euro area this year will be smaller than predicted by the traditional Taylor Rule – although greater than currently priced in by financial markets.1 It also points to relatively modest tightening by the Bank of Japan, which has recently abandoned its negative interest rate policy (NIRP).

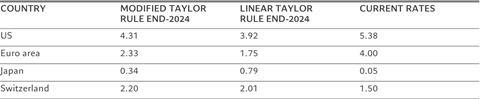

Fig. 1 - Rates outlook

Interest rate predictions based on linear and modified Taylor Rule, versus current levels

The US economy is now in the latter stages of its expansion phase, with activity expected to slow significantly later in the year. That points to interest rate cuts. Importantly, however, the US slowdown is not severe enough to prompt aggressive easing from the US Federal Reserve, particularly while inflation remains sticky and the labour market is strong. In light of this, our model shows that the Fed’s target rate could be reduced to 4.3 per cent by end-2024, which corresponds to around 100 basis points of potential easing. That is a smaller series of cuts than forecast by the traditional Taylor Rule, although it exceeds the 60 basis points priced in by financial markets.

For the European Central Bank, too, inflation is still in a range which historically has been a source of concern. That, our research shows, should mean more moderate easing than indicated by the traditional Taylor Rule, with the deposit rate likely ending the year at 2.3 per cent from the current 4 per cent. As for the US, markets are potentially underpricing the scope for cuts, with current levels pointing to rates finishing 2024 just above 3 per cent.

For Japan, our model suggests that Bank of Japan could hike rates to 0.3 per cent by year end. Exchange rate considerations – or more specifically the prospect that interest rate rises cause a sharp rise in the value of the Japanese yen – will likely prevent more aggressive tightening.

Switzerland, meanwhile, stands out as the exception. Both the traditional Taylor Rule and our modified version suggest that rates should be higher than they are now and that the recent cut in borrowing costs was not warranted as the Swiss National Bank did not really finish its monetary policy normalisation process back in 2023. The SNB indicated that the recent policy decisions have been taken from a risk management prospective – in this case the risk of not cutting rates and potentially allowing further Swiss franc appreciation was judged to be the most significant. This divergence between actual policy and our model could mark a new era for SNB policy as in previous years the relationship between the two had been relatively close.

Focus on the model

So how did we arrive at our conclusions?

We began by looking at ways to reconcile the fact that the traditional Taylor Rule is a linear model, but central banks’ policy isn’t. So the scale of the interest rate response to a 50 basis points change in the rate of nominal growth will vary in size depending on the actual level of growth. For instance, our analysis finds that Fed tends to react more aggressively when GDP growth is above potential and rate hikes are called for, than when it is below potential and cuts are needed. And there are other factors to consider besides growth and inflation. Take the aftermath of the Covid pandemic. According to the Taylor Rule, the Fed should have started gradually raising rates in 2021; instead, faced with uncertainty surrounding the post-pandemic economic recovery, the US central bank did not hike until March 2022, moving only after the fallout from the Ukraine war prompted an inflation surge.

What this shows is that no two situations are the same irrespective of the underlying economic fundamentals could provoke a different policy response each time it occurs.

Furthermore, forecasts for future growth and inflation usually incorporate a range of probabilities rather than a single definitive number, or parameter.

Then there are foreign exchange rates which have a strong relationship with inflation and thus with central bank policy. This is less significant in the US, which is a big economy that’s relatively closed and not very sensitive to exchange rate movements, but more of a factor for the ECB which has historically tended to cut rates aggressively whenever the euro has appreciated more than 2.5 per cent after adjusting for inflation.

The traditional Taylor Rule Is a “rough and ready” formula that doesn’t account for any of these complications. We believe its results would be more accurate if it did.

Our modified version of the Taylor Rule thus takes a nonlinear, semi-parametric approach, factoring in currency fluctuations and for the two-way interaction between exchange rates and inflation.

For Japan, our modifications include the addition of a variable that accounts for the importance of asset purchases in monetary policy; we have done this through M4 money supply growth, which shows the transmission of asset purchases into the broader economy. Historically, the Bank of Japan has responded much more aggressively when inflation has been high than when it has been low; it has also tended to offset any significant growth in M4 with policy tightening.

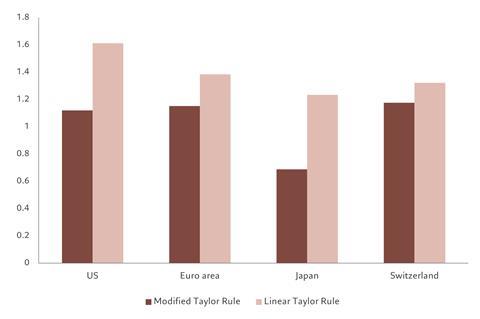

Having built our model based on data from late 1980’s (depending on the specific country considered), we then back tested it, for end 2014 to 2019, looking four quarters ahead at a time to see how effective it was – so called “out of sample” testing. Our analysis showed that, on average, the modified Taylor Rule predicted monetary policy more accurately than the original linear model, generating a lower root mean squared error (RMSE). This was true for the US, euro zone, Japan and Switzerland (see chart). Furthermore, the level of the error was also encouragingly modest, at below 1.2 for all four countries.

Fig. 2 - Reduced error

Root mean squared error for out of sample testing for our modified Taylor Rule model

After analysing data from the past 30 years, we find that the best fitting Taylor Rule specification for major developed and emerging central banks is nonlinear and semi-parametric2 model that incorporates an interaction term between inflation and the exchange rate, and, in the case of Japan, an additional M4 money supply growth term.

Moreover, our out-of-sample statistical analysis also shows that in most cases such a model permits more accurate forecasting of the upcoming central bank interest rate decisions in a real-time data setting compared to the traditional linear, parametric Taylor Rule.

Over the coming year, our model suggests less aggressive rate cuts in US and Europe, reflecting more prudent central bank behaviour, and more measured pace of rate hikes in Japan, than is implied by the original rule. However, for investors the key takeaway is that, even adjusted for the complexities of central bank behaviour, the cuts in US and Europe are likely to be more sizeable than currently priced in by markets. That offers an extra dimension on which to base valuation and investment decisions.

[1] Market pricing as of 08.04.2024.

[2] A semiparametric model is a statistical model that includes both parametric components and non-parametric ones (where we estimate smooth functions of variables instead of parameters).